Dark Matter (DM, often represented with the Greek letter χ) is a hypothetical particle that doesn’t interact with light, a particular feature that makes it very hard to observe. It’s existence is hinted at by a number of different phenomena, in particular the way galaxies rotate and collide, and where mass seems to be distributed across the Universe (inferred using observations of its gravitational influence). Basically, when we look out at the Universe, the maths tells us that there is more matter out there than can be seen - hence the name ‘dark’.

Now that we know (or rather, strongly suspect) there’s something out there, how do we work out what it is?

To categorise DM, particle physicists are interested in two things: its mass (m) and cross section (σ). The first term should be fairly self explanatory, but the second tells us how likely DM is to interact with regular matter, and how that interaction might occur (regular matter being what is described by the Standard Model of Particle Physics). One of the difficult things about DM is that physicists really aren’t sure what mass range DM should have, though some may have their own favourite pet theory. Because the possible mass range is so large, it is very difficult to build an experiment that can probe all of it at once. Instead, each experiment targets a smaller range, one bite at a time.

Image credit: an only half joking xkcd.

So once we have a mass range in mind, how do we go about measuring these values?

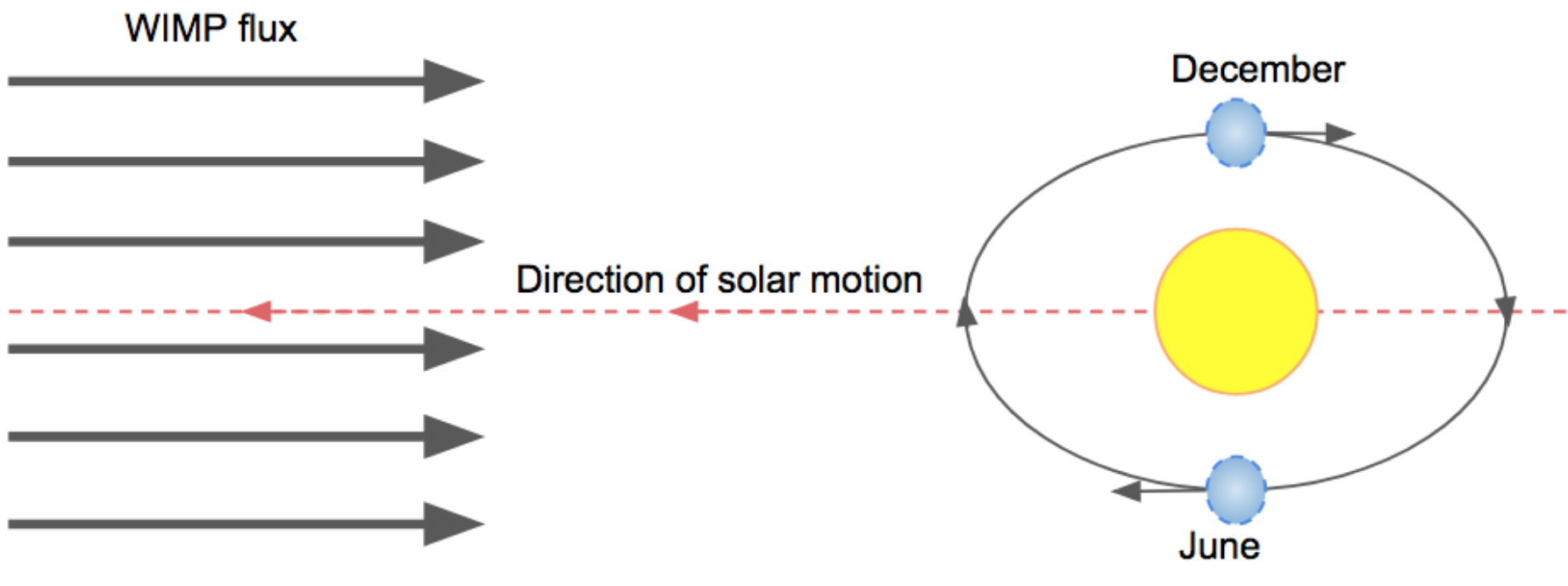

In general, there are three key approaches - ‘making’ DM via the collision of regular particles, observing the products of DM annihilation (‘breaking’ DM), or ‘shaking’ some kind of target and observing its recoil after collision with DM. I’m involved in a shaking search (also known are direct detection) called the SABRE Experiment. We are trying to observe a modulating signature - a signal that changes by ~1% throughout the year. This is due to the movement of the Earth as it rotates around the Sun, which itself is moving through a ‘galactic DM halo’, also called the ‘WIMP wind’. For part of the year (in June) the Earth is travelling with the Sun and so the DM will appear to be travelling faster than in December, when the Earth is travelling against the Sun and the relative velocity is a minimum.

Because the number of DM collisions wil scale with the relative velocity (think about how much more rain it feels like is hitting you when it’s windy), we expect the number of events to peak in June as well. This is a very particular signal that is difficult to mimic consistently with any background process, and so a good goal to search for in detection.

Image credit: Olena Shmahalo / Quanta Magazine

However, this is a very small change on an already tiny interaction rate - to observe it we need to watch for changes on the scale of 0.01 counts per day, per kg of target material. This requires us to create what some have described as ‘the most boring place on Earth’, an experiment in a laboratory space that has had the background reduced as much as possible to make sure that anything funny that is observed in our detector can be attributed to DM. Much of my work to date has involved calculating what the DM and background signals would look like in SABRE, and how well we might be able to tell them apart.